By Joe Wilkinson From the July/August 2007 issue of Iowa Outdoors magazine

By Joe Wilkinson From the July/August 2007 issue of Iowa Outdoors magazine

You may also be interested in How to Identify Iowa’s Poisonous Plants

There can’t be a worse feeling. The itch. The burn, almost sizzling at times. The ugly blotches and blisters on your arms, your legs...anywhere you contacted it. Poison ivy.

As the reddish dots spread over days, then turn into fluid-filled blisters and eventually scabs and scars, your skin becomes super sensitive. At first, it itches so badly you must scratch. Yet, to touch it is painful. Hot water, the lightest layer of clothing, even the air sometimes; any friction grates your skin, nerve endings and even your short-term mental health. Your blister-encrusted arms feel heavy. There seems to be no mercy for those of us afflicted by poison ivy.

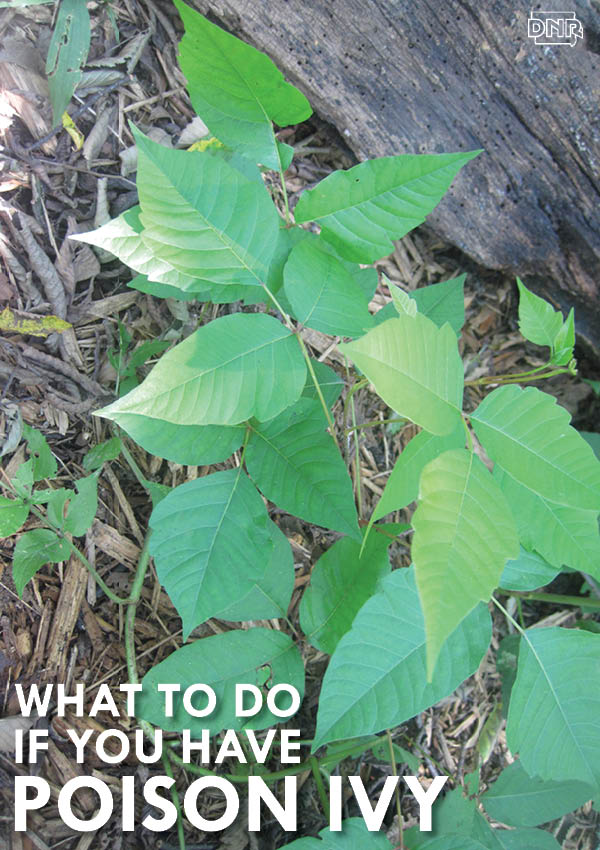

The “leaves of three” get plenty of blame for hot weather itching, and deservedly so. But a variety of plants, from wild parsnip to nettles, turn summer recreation into summer suffering for some. Various sources claim 60 to 90 percent of Americans are susceptible to poison ivy. Many of them—I’m one—are magnets for the stuff.

The ugly, itchy rash will go away in a few days. Treat it quickly to reduce the itching and misery. Dress properly, and avoid the obvious patches, bushes, vines and leaves and you might dodge the itchy bullet. And modern medicine answers the call, too. It’s not just “slather it with calamine lotion” anymore. Prescription medication, pre- or post-contact lotions, and various creams, oral applications and patches offer help from “the ivy.”

START FROM SCRATCH

Where does all that misery originate? Those reddish to light green to waxy, dark green leaves seem harmless. In the fall, the reddish-tinged green foliage is actually quite pretty. But it’s not something to pick and take home to Mom.

“The resin in poison ivy is very potent and elicits an allergic reaction,” explains Dr. Mary Stone, a dermatology professor at the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine. “The first time you are exposed, your body typically won’t break out. Your immune system learns to recognize it, though.” That’s why a 4-year-old playing in it might not develop a rash. Subsequent exposure, though, may cause breakouts. And it can get more severe over time.

That’s all a chronic poison ivy-sufferer needs to hear. I paid my dues the first 20 or 30 exposures. Or 40. So, while a significant minority—and the extra young—might not break out, others may scratch at a mere picture of poison ivy.

Count me in the latter group. By the time I was 13 or 14, I had poison ivy every month of the year. Winter? Yep. Stood downwind of a burning pile of brush. Smoke is a carrier. So are pets. I’m sure wrestling with my dog, Topper, after a day wandering in the fields and creeks caused a few outbreaks.

On the positive side, I could really gross out my five sisters and amaze neighbors with my temporary yet severe cases of leprosy. Nighttime was often a living hell, clean sheets every night turned pink by morning as the thick layers of calamine lotion rubbed off with my tossing and moaning. My brother, laying a few feet away, still has nightmares. Yet, except for my youngest sister, I can’t recall any of them getting it. Guess I took the bullet for the family.

OIL OF TURMOIL

“The oil from the plant can be passed along to you from secondary agents; garden tools, clothing, even pet fur,” says Stone. “A lot of times, that oil can turn black or brown. That could be a clue, but if it’s on a garden tool, it could look like dirt, too.” And don’t expect it to fade over time. Stone says the sap or urushiols can raise a rash for a year or more. That would explain a sudden facial outbreak one winter. I hadn’t been outside or anywhere near an itchy cache of leaves or brush. With a little mental backtracking, I figured out the rash around my eyes—sort of an itchy, blotchy raccoon pattern—matched the wool facemask I had worn a few days before. The last time I’d used it was the previous deer season. The resin remained active for 13 months.

Short of being one of the lucky immune few, or taking a desk job and spending free time in the house, how do you avoid it? Wash. And wash fast. The less time offending urushiols spend on exposed skin, the less severe the reaction. Common soap and water works well. So do pre- or post-exposure treatments, creams or other products applied to exposed skin. Do not take a bath. The damaging urushiols on your skin will mix with the steeping warm water, entering open pores. Instead, rinse with cool tapwater or shower.

When urushiols make contact with skin, it triggers an immune response. That “contact dermatitis” occurs as the urushiol makes its way through your skin. Your system metabolizes it and immune cells move to fight the foreign substance—the antigen. The inflammatory signals, or cytokines, alert white blood cells to fight the antigens. Sounds very efficient, but there is tissue damage; the reddish, blotchy rash that breaks out on your skin.

Most topical treatments are drying agents, aimed at reducing discomfort. A step up in treatment involves oral or injected medication, like anti-inflammatories and steroids. “Those more severe cases require an anti-inflammatory. They help suppress the immune reaction,” says Stone.

Those offending leaves, or vines, may have directly contacted one patch of skin. Or maybe urushiols on your fingers brushed across your face an hour later. Your delayed sensitivity will keep skin from breaking out for hours...or days. You don’t “get it” from the weepy blisters that break and ooze the disgusting liquid onto other areas. That’s a common misconception, says Stone. However, you should still keep them clean, even lightly wrapping in gauze to avoid infection.

You can stay indoors and avoid the stuff. The best advice, though, to avoid a long, hot itchy summer is to stay alert, wash quickly and remember all the surfaces the oils might inhabit while enjoying your time outdoors. Just remember, protect the “skin you’re in.”

Ouch! Nettles

A subtle scratch, followed by instant itching and burning. The culprit: stinging nettles. An herbaceous, perennial flowering plant, it is one of the first forest floor dwellers to emerge in the spring. There are two species, says DNR plant ecologist John Pearson. Stinging nettles (Urtica dioica) prefers sunny areas, while wood nettles (Laportea canadensis) leans toward shadier spots.

Covered in tiny hairs along stems and leaves, the hollow hairs release an irritating formic acid when brushed against. Like hundreds of tiny needles, the result is an intense itch and white, blotchy spots. Discomfort depends on skin sensitivity, but can last a few minutes up to 24 hours.

If you’re a budding botanist, find a healthy jewelweed, break the stem and apply the sap to affected areas, Pearson says. Although in a pinch, human spit has been said to alleviate some discomfort, baking soda and water paste works better. Keep a vial of the cooking companion on hikes to ward off itchy outbreaks.

Despite their painful bite, stinging nettles aren’t the devil in waiting. Red admiral butterflies covet these plants to provide a quick, easy meal for emerging offspring. Steeped in several changes of water, nettles are a tasty substitute for tea leaves or an alternative to a spinach salad. And don’t throw the boil away. The water, loaded with formic acid, makes a good organic pesticide against mites and aphids.

Pick your poison

Poison ivy so often gets the rap when the bubbly, painful rashes show their evil side. But in recent years, wild parsnip has taken up the villain’s cloak. The culprit for painful breakouts when poison ivy is nowhere to be found, this Eurasian import is often found in road ditches and out-of-the-way corners of yards and wild areas or disturbed areas where it spreads. With 5 to 15 sawtoothed-edged leaflets, the little rosettes hug the ground the first year or two, eventually growing to 4 feet or so. And it can be vicious.

The deal breaker between wild parsnip and poison ivy is sunlight. As you walk through a patch of parsnip, leaves and sturdy stems leave scratches on exposed skin. It’s “sap,” called psoralen, reacts with sunlight. Too much psoralen and sun, and you’ll have red, streaky—and painful—outbreaks. “Wild parsnip will cause a streaky rash,” says Stone. “To the expert eye, it looks different. It’s not as ‘blistery’ as poison ivy.” The experts refer to it as “phytophotodermatitis,” a very long word that means the plant reacts with sunlight to make your skin itch. That short Latin lesson might put your mind at ease, but your dermis is screaming in pain.

The blotches are an allergic reaction, so treatments similar to poison ivy work.

****

EDITOR'S NOTE:

No poison oak or poison sumac in Iowa

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans and Toxicodendron rydbergii), poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum and Toxicodendron pubescens), and poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) all contain the same toxic oil named urushiol, which causes a red, blistering, itchy rash. This common thread can lead to the assumption that you've had a brush up with any of the three, but having a rash does not by itself indicate which species you encountered.

Poison ivy is very common in Iowa, but poison oak and poison sumac have never been documented by botanists in the state. Maps of plant distribution

Disagreements about which species occur in Iowa has to do with the difference in the way that botanists and the most people classify these species. Botanists use the terms is a narrow sense that applies the name “poison ivy” to two species that do occur in Iowa and restricts the names “poison oak” and “poison sumac” to species that do not occur in Iowa.

Many other people in contrast, use these same names in a much broader sense, applying the terms “poison oak” and “poison sumac” to what botanists would classify as poison ivy. Arguments over the use of common names of plants can be never-ending because so many people call the same plant by different names. This is why scientific names (the italicized Latin names that follow the common name in parentheses) are more useful for precise discussions. In this article, we are following the narrow sense used by botanists. Comparison photos illustrating the differences recognized by botanists

In Iowa, fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica) may be often confused for poison oak, but it's not poisonous. It also grows in the same habitat as poison ivy - possibly leading people to get a rash from the ivy, then mistakenly attribute it to the plant they saw that resembles poison oak. Botanically, the genus Toxicodendron (which contains poison ivy, poison oak and poison sumac) and the genus Rhus (which contains the true sumacs) are in the same family, so they bear a resemblance to each other. However, only the Toxicodendron species are poisonous, the Rhus species are not (except for especially sensitive people).

While Iowa has some poisonous plants, don’t let it keep you out of the woods. Stay on groomed trails and paths until you feel confident in your identification skills.